The Bach Tuba Project: What is this, anyways?

Note: As you’ll read below, there has been a fair deal of tinkering, planning and experimenting going on. As such, we are a few weeks behind and this week’s entry compresses several weeks’ work into one.

I think one of the great challenges in crafting a “research” project around an applied art form like music performance is figuring out how to place it neatly within the requirements and expectations of a program that traditionally caters to projects and research done in more “conventional” settings such as a laboratory. As musicians, I think we sometimes have a precarious place within academia: one foot in the ivory tower, and the other in the concert hall…Which is to say that our conversations about how in the world we could make this proposal work were broad, a bit circuitous and oftentimes a bit confusing. Whereas we had initially crafted a proposal back in January that was accepted, once May came around, we were both struck with the somewhat looming question: “What is this, anyways?”

In working through this project, we began with some overarching themes that underpinned our proposal: 1) exploring how interdisciplinary studies could fit within tuba performance; 2) studying the (selected) works of J.S. Bach; 3) considering if/how we could apply this interdisciplinary “approach” to other facets of our tuba playing. One of the central challenges in the first few weeks was deciding on an entry point: with such a broad topic, where does one begin?

Over the next several meetings, we began by addressing several simple prompts to help refine our project:

Summarize our proposal and project in approximately 30 seconds-1 minute as if you’re speaking to someone who is educated, but not within our field (music).

Explain the knowledge gap this addresses for you.

Explain the knowledge gap this addresses within our field.

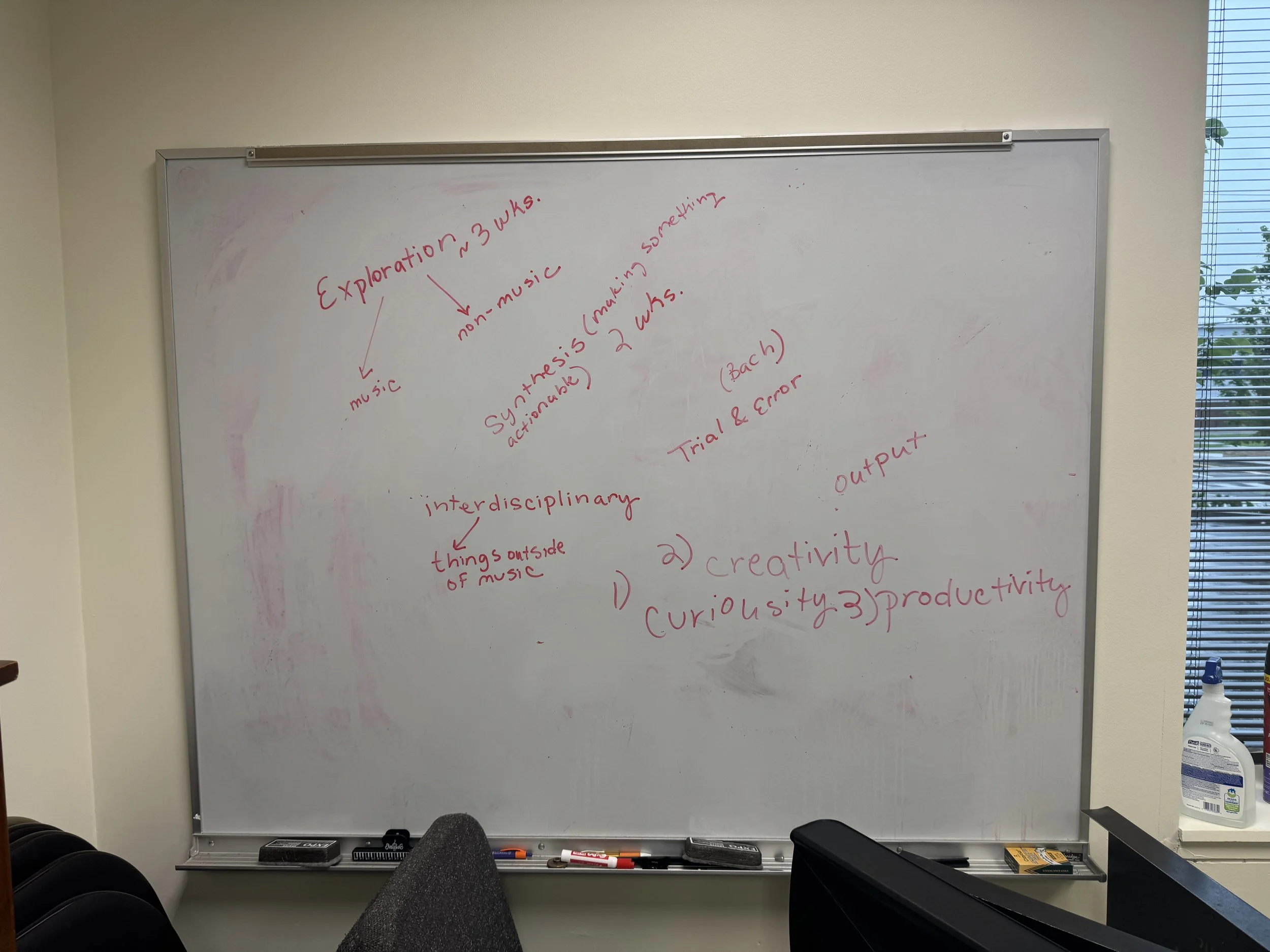

Throughout our work, we’ve kept a fair number of notes both digitally and physically, via whiteboard. After our first meeting, here was our initial progress:

So, we had a ways to go after that first meeting! However, something interesting emerged – in reading Ally’s and my responses to those three prompts (see above), quite a bit of overlap emerged:

Ally’s Responses:

Creates a “smart” approach to practicing, resulting in more efficient practicing and an overall better performance

Currently feel like I don’t have much of a rhyme or reason to practicing and end up wasting time and tiring my face

Develop an approach to tuba that goes beyond just playing and taps more into the mental and knowledge side of things

Existing approaches to tuba (e.g., method books) usually only address the playing side of things through technical exercises; conversely, others are only written text; there are few to no resources that combine text with musical examples

In our studies, we typically look at music theory or musicology or psychology as independent from applied performance; there is little emphasis in music school (generally speaking) to incorporate these facets of knowledge into playing, despite many music schools having a “liberal arts” curriculum

Beth’s Responses:

Our goal is to develop, refine and articulate an approach to practicing that inspires tubists to be independent, thoughtful, creative and curious musicians. This approach will be refined and demonstrated using work by J.S. Bach.

As a teacher, I struggle to make music relevant to students beyond their ability to accomplish something through music. Is this my job? Not sure, but I think it would make my teaching more relevant for students. In my observation, students work very hard, but sometimes not efficiently or intelligently. The old adage of “work smart, not hard” is nice, but I feel few have taken the time to explain what that means in our field.

See above.

This was a valuable lesson for me: begin with the simple (and sometimes perhaps obvious) questions, and look carefully at the answers. From this conversation and our independent exploration after that first meeting, our project began to slowly take shape:

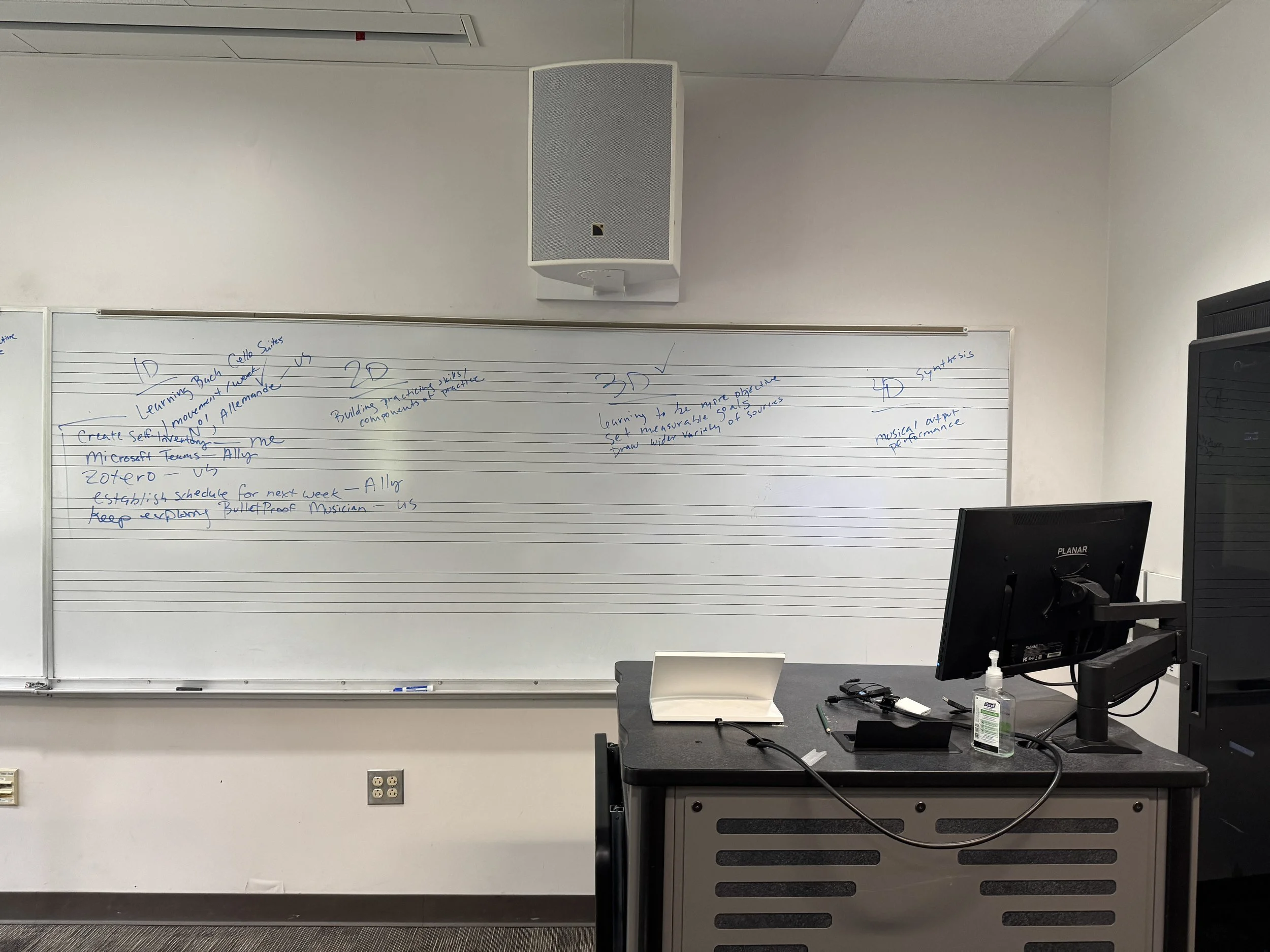

In the several meetings that followed, a semi-solid plan moving forward began to emerge:

Each week, we would choose a different movement from Bach’s cello suites to study

We would both practice the “assigned” movement for each week

We would choose a topic (rhythm, harmony, etc.) that would be the central focus for the week and consider how that topic can inform our approach to Bach’s music and how it might also be viewed through an interdisciplinary lens (e.g. researching rhythm in sports, etc.)

We would collaboratively create a social media account (Instagram) for sharing our practice, research and performances. The goal here was to hold ourselves accountable, record regularly, create content that would inform thoughtful practicing and encourage an interdisciplinary approach to tuba performance.

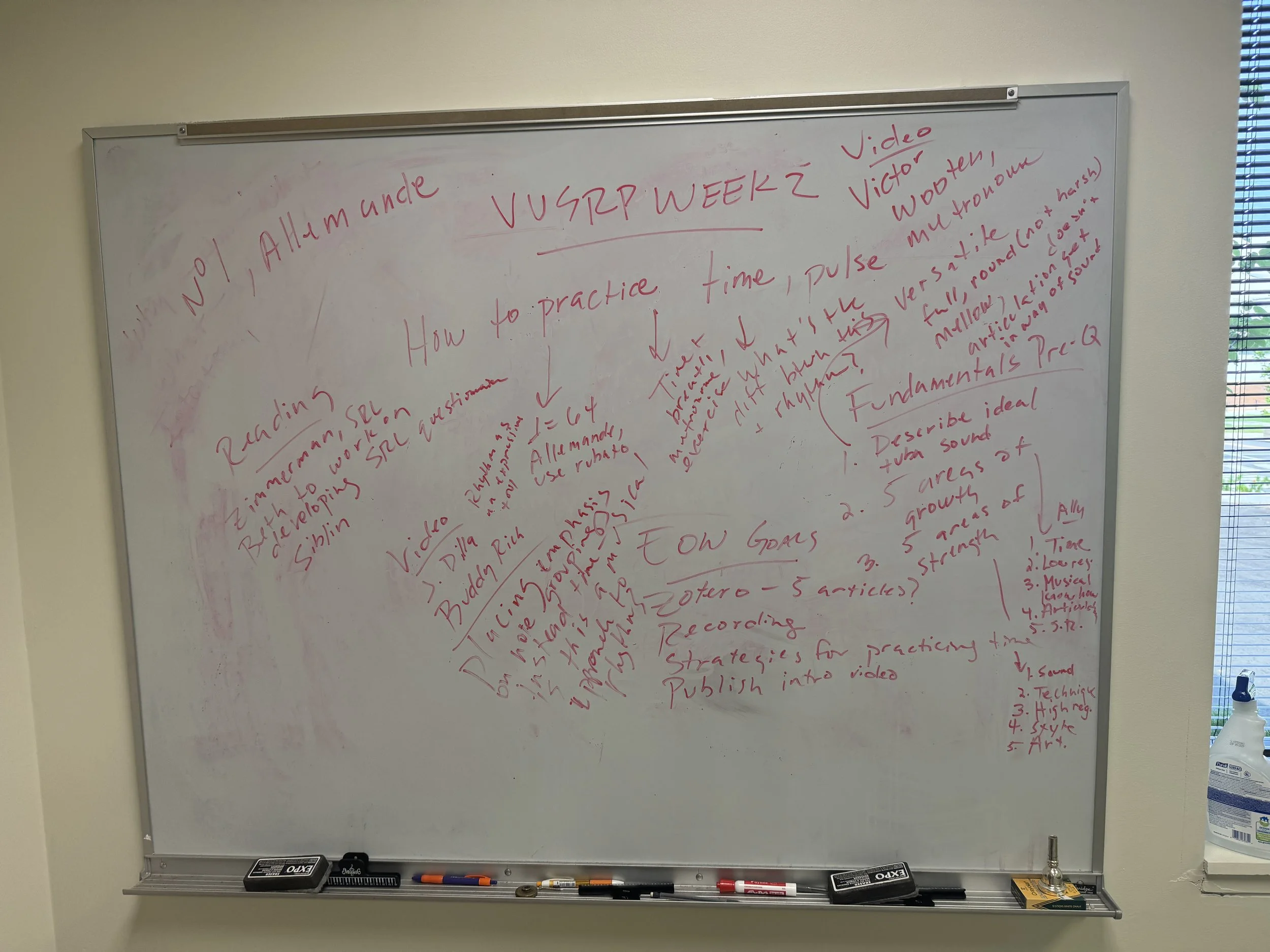

Below is a glimpse into our weekly agenda for the first week of this project: digging into the concepts of rhythm, time and space in Bach’s Allemande from his first unaccompanied suite in G major:

I should mention that, while our project is focused around Bach’s music we do, in fact, practice and work on other repertoire throughout the week. That’s even kind of the goal – using an approach to Bach to inspire and inform the way we approach other repertoire. Each meeting began with sight-reading and fundamentals on CC tuba, then transitioned into Bach and then other repertoire that Ally is working on for upcoming auditions and solo competitions.

In rereading our notes – and we have copious notes from each meeting in a shared Google doc (thanks, Ally) – I found a passage from a text I had discovered early in the week exploring Bach’s Allemande. The text was excerpted from a biography of J.S. Bach by Johann Forkel, an early Bach biographer:

Most youthful composers let their fingers run riot up and down the keyboard, snatching handfuls of notes, assaulting the instrument in wild frenzy, in hope that something may result from it. Such people are merely Finger Composers—in his riper years Bach used to call them Harpsichord Knights—that is to say, their fingers tell them what to write instead of being instructed by the brain what to play. Bach abandoned that method of composition when he observed that brilliant flourishes lead nowhere. He realised that musical ideas need to be subordinated to a plan and that the young composer’s first need is a model to instruct his efforts.

—Johann Nikolaus Forkel, Johann Sebastian Bach (1802, 70-71)

I found this passage especially insightful as a performer because it reminds us of the important role our brain plays in performance. This week, our task was to examine the difference between rhythm, time and space — both generally and in Bach’s Allemande from his first suite. As part of this week’s interdisciplinary explorations, I researched how rhythm is utilized in other disciplines. Along the way, I discovered a fascinating aspect of this research, which was the concept of entrainment — how one system’s behavior influences and/or synchronizes with another. The idea of auditory-motor integration follows this principle, linking auditory perception with motor control through vast and complex neural and cognitive processes. Which is to say, tl;dr: playing music is complicated and involves synchronizing many facets of the human brain and body. Consequently — at least for myself — fine tuning how we approach the process of music-making can pay dividends for our musical progress. Can focusing on the input have a real impact on the output? Stay tuned, as we consider this topic next week…