The Bach Tuba Project: Thinking about an interdisciplinary approach to applied lessons

I bought my first house in 2016, just as I was concluding my first year teaching at Appalachian State University. It was a great little house and in excellent shape, but it did have particularly treacherous stairs leading up to the front (and only) door. Google tells me these stairs were called “box frame stairs” and were a set of 23 wooden-framed stairs built into a hill and empty in the middle, making them sturdy and functional, but dangerous. They looked a bit like this (not my actual stairs, but a similar representation):

One of the first projects I decided to tackle was the task of filling each of these stairs with gravel to make each stair level and more attractive. On my first trip to Lowe’s, I picked up a bag of “riverstone” that I thought was particularly nice, and set to work. With a weight of 50 pounds per bag, it was not a light chore, but I still figured it was the best option.

Here’s where the challenges began: naively, I had assumed that I would need about one bag of stones per stair. That, multiplied by the 23 stairs on my property, seemed like a tedious, but manageable task. However, I quickly learned that it actually took 3-4 bags of stone per stair to adequately fill each gap. That meant I needed anywhere between 69-92 bags of stone! Moreover, I drive a small hatchback sedan, so I could only fit 4-5 bags of rocks in my car at any given time, and the Lowe’s was about 30 minutes away from my house.

Seeing no better option at the time, I began routine trips to Lowe’s to pick up my rocks, 5 bags at a time. At 250 pounds per trip – not to mention cost (about $5-6 per bag), this became an all-consuming, exhausting, expensive and seemingly never-ending process that consumed my life for several months. When I emptied that final bag of rocks, I felt a great sense of accomplishment, but could also see the downsides to my work immediately: there was gravel everywhere, and I could tell this would only be a temporary solution. I saw that I was right the next spring, after the snow had melted and the soil had resettled. I would need more rocks to once again make these stairs even, and the maintenance would be continuous as long as those stairs were there.

Eventually, I decided this was silly, cumbersome and I didn’t want to spend my entire paycheck on – literal – rocks. So, I asked my father for help. My father is an excellent craftsman and had said – more than once – that a cheaper and more effective option would be covering each stair with wood. I hadn’t considered this option previously because I didn’t own a saw and thought that option seemed far more complicated than “just a few bags of rocks.” But now, I was ready to reconsider. In a cruel twist of fate, the first step in doing this project the “right” way was removing all of those rocks.

The reason this story came to mind is because of the familiar feelings of frustration, endless work, and temporary (and mediocre) results. As a student towards the end of my undergraduate career, I felt like I had worked exhaustively, was a long way from being finished and lacking a clear sense of “what next?” As a teacher, I now see this overwhelmingly in students. Particularly as students begin the tedious task of taking multiple auditions, I see how hard they work and how devoted they are to their craft, but also how – if I am being honest – there are basic skills that are frequently still missing.

If I were to fix that staircase again, I would begin by having a clear plan, calculating how much wood I would need, figure out the appropriate tools, then learn how to use them prior to undertaking the larger project of 23 stairs. Probably ask some folks for help along the way, too. It may have involved more investment of time and acquisition of skill in the beginning, but would have ultimately been faster and a more lasting solution in the long-run. Is there a way to relate this approach to music? I think so, and to me, this demonstrates the basic principle that approach has a great impact on outcome.

Each week, Ally and I have chosen a single movement of a Bach cello suite and a topic with which to build our work and approach to that week’s repertoire. Here is our “rough draft” list of topics, followed by our list of repertoire for the summer:

Topics

The difference between rhythm and time/strategies for improving both.

Play fast, think slow? Strategies for making technical passages feel and sound easier.

How to discover, build and shape a phrase. Drawing parallels across disciplines to simplify the concept of phrasing (e.g., relating phrasing in music to punctuation in grammar)

How understanding and discovering harmony can help our intonation.

Using Bach’s music to address technical challenges on our instrument. (e.g., transposing down several octaves to work on low register, working on high register, etc.)

Building listening habits on and away from the instrument.

How studying Bach (and performances of Bach) can influence our approach to tone.

How our approach to Bach can be applied to other repertoire.

Repertoire

Allemande, Suite No.1

Gigue, Suite No. 3

Bourrées I & II, Suite No.4

Courante, Suite No.2

Sarabande, Suite No.6

Prélude, Suite No.5

The idea for this approach stemmed from our discussions regarding differences between textbooks and method books. One main difference we identified was the information that was delivered alongside the musical examples/material: whereas method books typically featured only music or limited prose/commentary, textbooks were built around information and, more specifically, generally organized by building upon concepts.

With this observation, we wondered: would it be possible to structure our weekly lessons/meetings/work in a method that combined the more “concept”-based approach with that of the typical applied lesson setting? Could this strategy be applied across our summer goal of studying Bach’s cello suites?

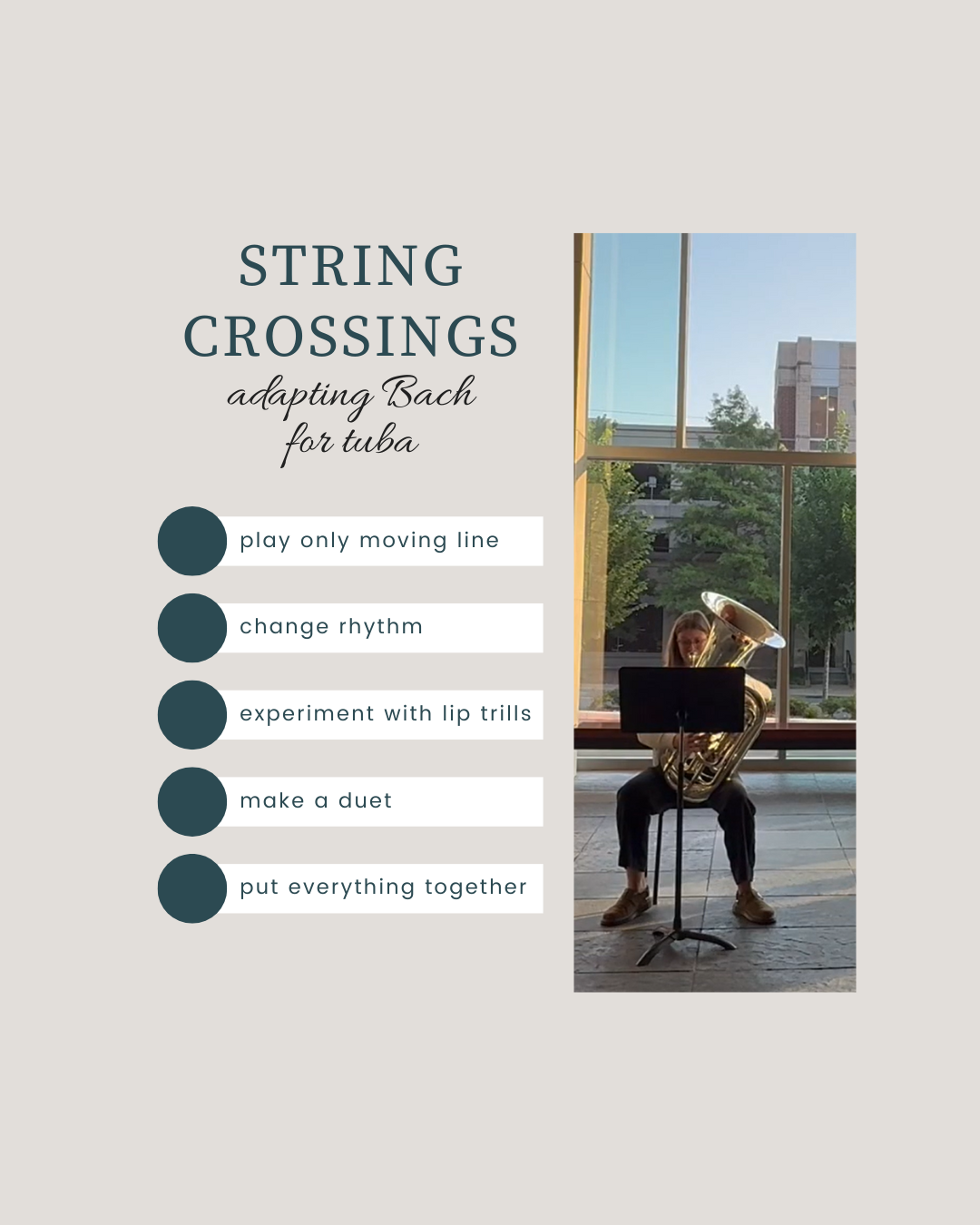

As a teacher, I found this structure difficult to navigate in the beginning, but deeply meaningful as we progressed. One aspect that has been surprisingly enjoyable and useful is social media. It’s been tremendously useful for helping to identify and articulate the main points of our research, clarify the most important aspects of a given topic, and think about our audiences when writing/recording/performing/presenting material. As an example, here is a slide from one of this week’s posts, illustrating strategies for practicing an important topic within the Gigue from Bach’s third cello suite:

Ally created an accompanying video to go along with this slide, further demonstrating and discussing how one might go about approaching this difficult aspect within Bach’s work. As a teacher, I found this to be really neat – it demonstrates a clear strategy that can be utilized across multiple pieces, breaks down and articulates steps within the process, and includes a performance of the passage that exemplifies mastery of the concept. To me, what is exciting is the independence and critical thinking this requires and cultivates: it has been so rewarding and interesting over the course of the summer to see what parallels are drawn between repertoire, topics, technique and more.

While there is much positive I have learned, I believe we have also discovered some challenges. Pacing has proven to be a challenge, especially as the outside demands of the end of summer and beginning of the new year approach. How can one effectively combine this more “theoretical” or conceptual approach with the practical demands that learning new repertoire requires? It is both easy to forget the repertoire at hand when navigating difficult concepts such as the nuances of time and rhythm; and likewise easy to forget the overarching concept you are working on when faced with a multitude of other challenges within a given piece. Like so many things within music, balance has proven to be essential.

This week’s topic was – broadly speaking – “input impacts output.” It’s a slightly cliché and broad way of saying that the manner with which we approach a task – in this case, practicing and playing our instruments – has a direct impact on the final result. Throughout the week, we brainstormed and workshopped strategies that emphasized this concept and could be applied directly to Bach’s music, then looked at how the study of similar concepts within psychology could aid our understanding of this topic. For many of us, I found this to be a prescient reminder of the value in thinking about how we approach a task and considering how that may affect the final product.

I thought there would be no better way to conclude this story than with a photo of the now-complete (and I have since moved) stairs: while simple, they represent years of hard work, some help (thanks, Dad) and much learning. Happy practicing, all!